Henry Kissinger, a German-Jewish descent whose life and future were significantly influenced by the rise of the Nazis led by Hitler, emigrated to the United States with his family during his teenage years and settled in New York, in a neighborhood predominantly inhabited by Jewish immigrants.

With the victory of Richard Nixon, the 37th President of the United States from the Republican Party in the 1968 elections, the ambitious Kissinger was appointed National Security Advisor. His fortune shone brightly, and his fame as one of the designers of U.S. foreign policy spread in the political world, linking his name with many significant events of the 1970s.

Ending U.S. military intervention in the Vietnam War, successfully establishing relations with Maoist China by exploiting the rift between China and the Soviet Union, Nixon’s visit to China and meeting with Zhou Enlai and Mao Zedong, signing the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (SALT) with the Soviet Union during the Brezhnev era, bombing Cambodia, U.S. support for the military coup in Chile in 1973, supporting the Argentine military in suppressing and killing civilians, supporting Pakistan in its bloody conflict for independence from Bangladesh, openly supporting Israel in the Yom Kippur War with the Arabs, and efforts to end the conflict in 1973, forging friendship and alliance with the Shah of Iran, and making Iran the regional police force while selling billions of dollars worth of arms, and eventually encouraging and secretly supporting the Kurdish uprising in Iraq led by Mullah Mustafa Barzani only to abandon them in their most critical moments are parts of U.S. foreign policy during the Cold War in which this ambitious and influential American-German diplomat played a crucial role as an architect and the real cause of these transformations during his official presence in the power structure from 1969 to 1977, holding two key positions: National Security Advisor and Secretary of State during the Nixon and Ford administrations. In the subsequent decades and until his death, he continued to strive for securing U.S. and its ally Israel’s interests, authoring several books and hundreds of specialized articles, and establishing a consulting firm to advise all U.S. Presidents regardless of their party affiliation. His influence was so significant that George W. Bush remarked on his death as “the silence of one of America’s most important and resonant voices in foreign policy.”

This degree of influence, combined with ambition, placed his character under various and sometimes contradictory judgments. Western politicians and statesmen regarded him as an outstanding and unparalleled diplomat, while lawyers and human rights activists viewed him as a heartless politician accused of war crimes.

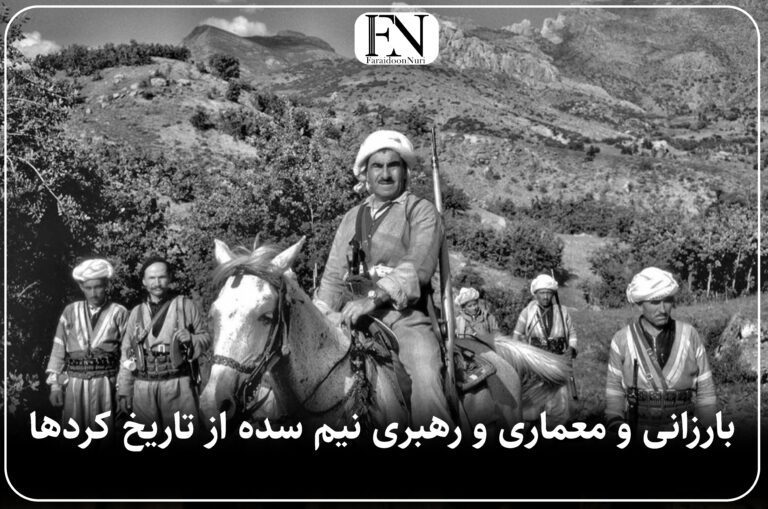

For the Kurds, however, he symbolizes the ambitious and unethical realism in U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East, his name being associated with the bloody and disastrous collapse of the Kurdish uprising against the Ba’athist regime in Iraq in 1975. As Larry Everest, a leftist, elaborates in the book “Oil, Power, and Empire – Iraq and the Global Ambitions of the United States,” in the chapter on Kurdistan, he details the betrayal of the Shah and America towards the Kurds. He correctly believes that with Kissinger’s presence as the architect of U.S. foreign policy, the Kurds, led by Barzani, after years of struggle, forced the Ba’ath government on March 11, 1970, to sign an agreement to establish an autonomous region in Kurdistan, recognizing some of their cultural national rights.

According to the agreements, Kurdish rights were emphasized much more extensively and legally compared to America’s two regional allies, Turkey and Iran. The Ba’athists’ inclination towards the Soviet Union and signing a friendship and cooperation treaty with this superpower in 1972, along with fueling Arab nationalist sentiments and hostility towards Israel, alarmed America and its regional police force, Iran, prompting them to consider playing the Kurdish card to weaken the Ba’athists.

During this period, shortly after the agreement between the Ba’ath regime and Kurdish representatives, it became evident that critical issues like Kurdish control over local security forces, receiving a fair share of oil revenues, and participation in the national power structure remained unresolved. The Ba’ath regime also began an Arabization program in oil-rich regions, even attempting to assassinate Kurdish leader Mullah Mustafa Barzani. Such policies frightened the Kurds and completely eroded their trust in the Ba’ath regime. Barzani had been in contact with the U.S., the Shah, and other countries long before and had sought assistance against Baghdad. He even promised in a Washington Post interview that “if America protects us from the wolves, we are ready to align with U.S. policy in this region. If the support is strong enough, we can control the Kirkuk oil fields and give it to an American company to work in.”

In 1972, the Shah and Kissinger implemented their plan to use the Kurdish card in Iraq, leveraging Baghdad’s non-compliance with the agreements, providing controlled financial and military aid to the Kurds, and encouraging Barzani to restart the uprising against the Ba’athists.

The visible and hidden interventions by the Shah and Americans poisoned and further darkened the already fragile and unstable relations between the Kurds and the Ba’athists, turning the last hopes for maintaining a fragile peace in Kurdistan and Iraq into despair. Eventually, in March 1974, with the support of the Shah of Iran and America, Barzani initiated a new conflict against the Iraqi government, initially achieving significant victories.

Detailed reports by Otis Pike, a New York representative in the U.S. Congress, on U.S. and CIA intervention and Kissinger’s role in the Kurdish-Iraqi conflicts, along with a confidential letter from Kissinger to Richard Helms, the then U.S. ambassador to Iran, which was released by the Nixon library archives in recent years, regarding the extent and nature of U.S. aid to Iraqi Kurds, are two crucial historical documents demonstrating the devious policy and approach of Kissinger and the Shah towards the Kurdish uprising in Iraq.

Kissinger’s letter to Helms in 1974 shows that Kissinger and the Shah did not want an all-out war or the collapse of Iraq. Instead, they wanted to force Iraq to stop cooperating with the Soviets and show others in the region that aligning with the Soviet Union was futile. Moreover, the Shah aimed to demonstrate that Iran was the strongest power in the Persian Gulf and the most reliable regional police force for implementing U.S. policies. He also sought to revise the Saadabad Treaty, which had granted control of the entire Shatt al-Arab waterway to Iraq.

Kissinger explicitly stated to Helms that creating an autonomous and independent Kurdish state in Iraq and permanently partitioning the country would not bring long-term economic benefits, and neither Iran nor the U.S. intended to sever all relations with the Iraqi government, which certainly offered significant benefits for both countries.

The year 1975 was pivotal. While the Kurds, supported by Iranians and receiving aid from the U.S., had achieved significant victories, with tens of thousands of Kurdish Peshmerga tightening the grip on the Iraqi army with military and logistical support from the Shah, rumors and scattered reports about secret negotiations between Iran and Iraq began to surface. Even Sadat subtly hinted to Barzani’s representatives about a possible agreement between Saddam and the Shah, recommending reconciliation with Baghdad.

Despite complete distrust of the Shah, Barzani considered the relationship with America and receiving aid from them as a guarantee of continued support. Unwisely, he was misled by American support and Kissinger. The OPEC summit in Algiers, attended by the Shah and Saddam, marked a tragic end for Barzani’s relations with the Kurds and the Shah, Kissinger, and the CIA, turning into a horrifying nightmare for the Kurds.

The Shah and Saddam embraced, facilitated by Boumediene, and the Shah traded the Kurds for his long-standing enemy. Shortly after Iraq agreed to the terms formulated in the Algiers Accord in 1975, the Shah and the U.S. cut aid, including food aid, to the Iraqi Kurds, closed the Iranian border, and blocked the Kurds’ retreat route. The Kurds, not imagining being abandoned so quickly and easily, were betrayed by the U.S., who coldly turned their backs on their Kurdish “allies.” According to Pike, the American malevolence towards their ally hadn’t reached its peak yet! Barzani wrote a letter to Kissinger, desperately pleading for help, but Kissinger didn’t even bother to respond. In letters written later, during his stay in the U.S. for medical treatment, addressed to the next U.S. President (Carter) and Congress representatives, Barzani bitterly and disappointedly complained about the Americans’ behavior towards the Kurdish movement. He, like Pike, believed that Kissinger and the Shah had betrayed him.

Clearly, America’s goal wasn’t the Kurdish victory or self-determination. The CIA feared this strategy might prolong the rebellion and strengthen separatist sentiments among the Kurds, giving the Soviets an opportunity to create problems for America’s allies (Turkey and Iran). As in the 2017 Kurdistan referendum, the Americans didn’t support Kurdish self-determination and independence. According to Barzani in a recent interview with Al Jazeera, then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson explicitly opposed the referendum and stated that if it were held, the areas under Kurdish control would be limited to the 1991 borders. Events after October 16 of that year indicate that America’s 1991 policies towards Kurdistan still align closely with Kissinger’s views. Pike’s detailed report on U.S. intervention

in the 1975 Kurdish uprising and Kissinger’s letter to Helms confirm that Kissinger’s devious policy and approach had nothing to do with the Kurds’ freedom and self-determination, and these tactics aimed to ensure the political security of Iran and America and the economic benefits of both countries in the region. Kissinger said that one should always consider three key points in foreign policy: never forget that states have no friends, only interests; never leave anything important in the hands of others; and be wary of trusting anyone who doesn’t share these principles. This statement, attributed to a former U.S. Secretary of State, is as relevant today as it was half a century ago.

However, for the Kurdish people, their new experience was bitter and costly. The aftermath of the betrayal by Kissinger and the Shah, along with America’s abandonment, led to the death, displacement, and devastation of hundreds of thousands of Kurdish families. Many fled to Iran, where they faced difficulties and hardships, while others remained in Kurdistan, enduring the Ba’ath regime’s inhumane treatment.

Kissinger’s role in U.S. foreign policy, especially in the Middle East, has left an indelible mark on history. His actions, particularly the abandonment of the Kurdish cause, reflect the harsh realities of geopolitical strategies where alliances are temporary and interests often outweigh moral considerations. The legacy of such policies continues to resonate, influencing current international relations and the ongoing struggle for Kurdish self-determination.